TypeScript —

Make types “real”, the type guard functions

Make types “real”, the type guard functions

Photo by https://unsplash.com/photos/qTLyiHW1nIc

This article is part of the collection “TypeScript Essentials”, Chapter six.

People thing that , at runtime, all the gains of types are loss. In this chapter, we will see together that this is totally untrue.

The previous chapters showed us all the principles we need to master in order to write maintainable and powerful types.

However, TypeScript is often resumed as “only being a static type checker”, meaning that, at runtime, all the gains of types are a loss.

In this chapter, we will see together that this allegation is totally untrue.

However, TypeScript is often resumed as “only being a static type checker”, meaning that, at runtime, all the gains of types are a loss.

In this chapter, we will see together that this allegation is totally untrue.

The lack of runtime type checking/assertions

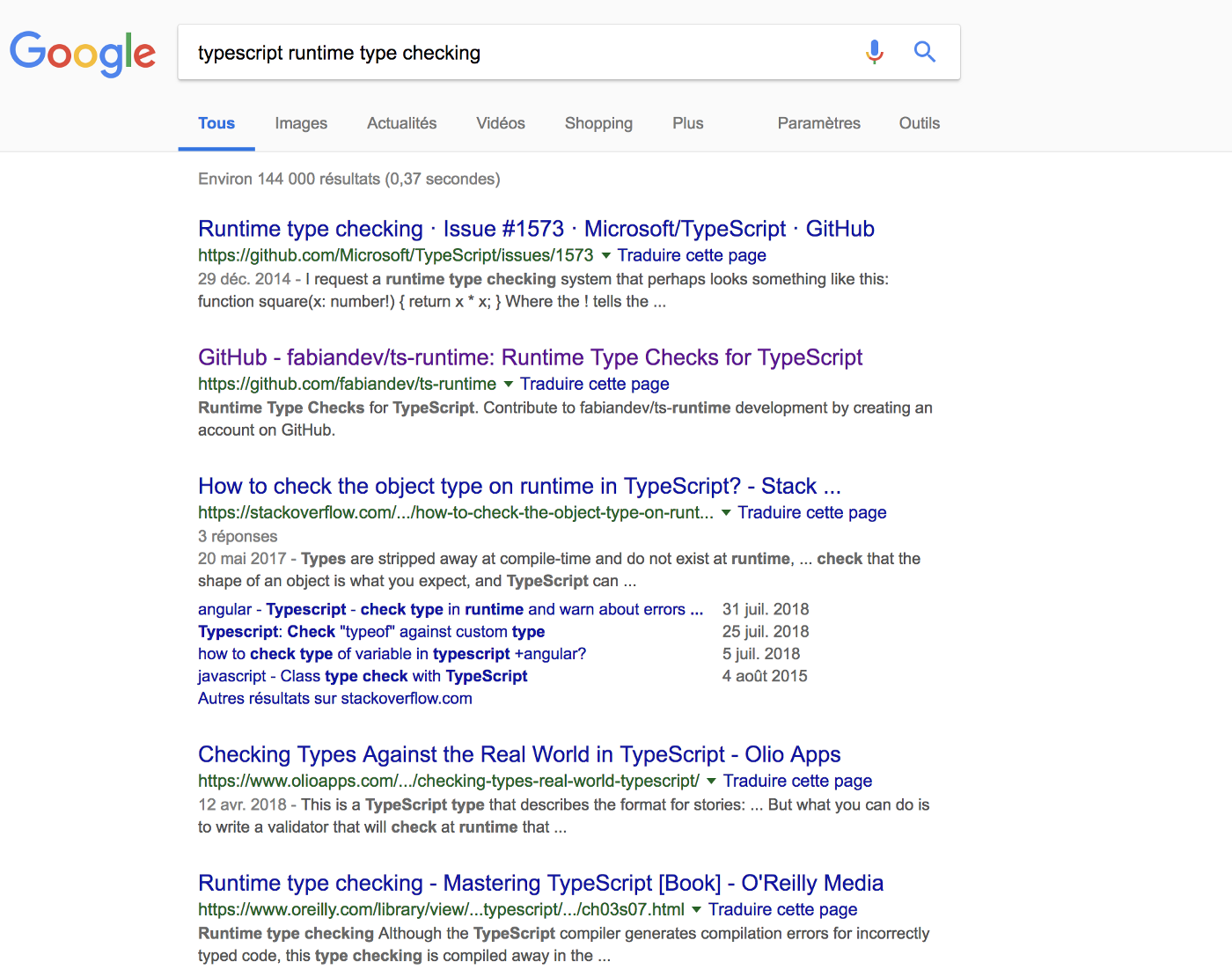

One historical blame on TypeScript is the lack of “runtime checking”.

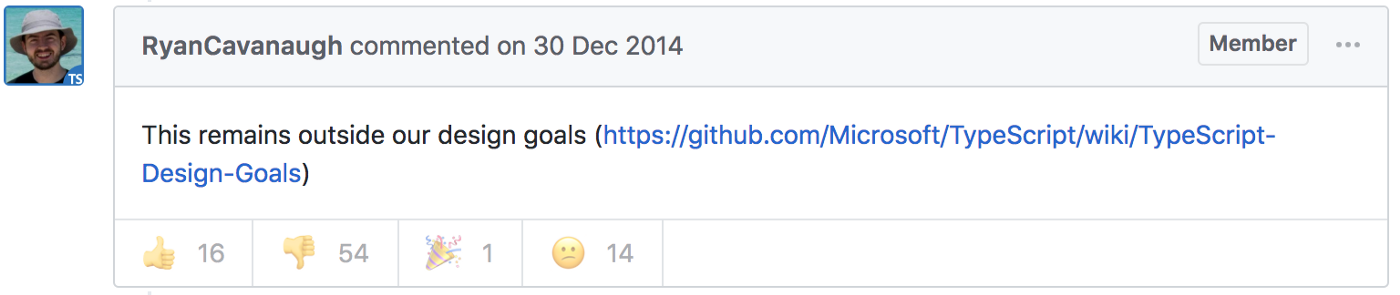

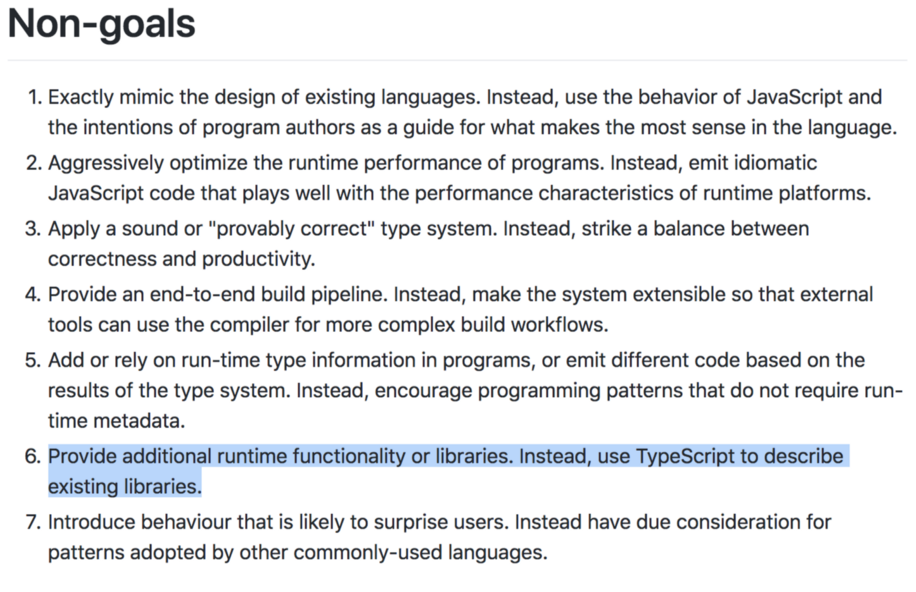

The answer to this “runtime type checking” topic from the TypeScript core team is clear:

Let’s look at the TypeScript design goals regarding runtime type checking:

TypeScript aims to not have any impact on the runtime and also preserve runtime behavior.

We will see that this is not a fatality, because TypeScript is more powerful than you thought and some developers of the community are very crafty.

Here comes Type Guards

First, what does mean:

“making types real”

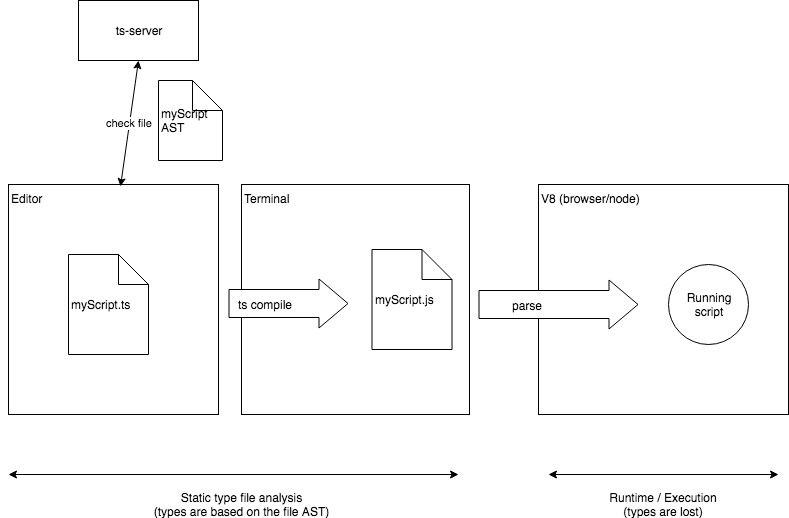

As you noticed, TypeScript does a static analysis of your code to infer types (“guess” types based on function calls, variables tracking, basically the AST),

which make it impossible to, for example, create types based on the script running behavior (for example: “if this object have this dynamic property, then this is a MyType type).

which make it impossible to, for example, create types based on the script running behavior (for example: “if this object have this dynamic property, then this is a MyType type).

Difference between script as a file and script at runtime.

This “gap” between what we call “runtime” and “static analysis” can be filled using TypeScript Type Guards.

TypeScript provides 2 way to do Type Guards:

- by using instanceof and typeof JavaScript operators

- by creating “User-Defined Type Guards”: defining your own type assertions using Functions,

“instanceof” and “typeof” Type Guards

typeof

Considering the following formatMoney function that accepts a string or a number:

1function formatMoney(amount: string | number): string {

2 let value = amount; // **value** type is number or string

3 if (typeof amount === "string") {

4 value = parseInt(amount, 10); // **amount** type is string

5 }

6 return value + " $"; // **value** type is number

7}These _typeof_ type guards are recognised in two different forms:

typeof v === "typename" and typeof v !== "typename", where "typename" must be "number", "string", "boolean", or "symbol".

While TypeScript won’t stop you from comparing to other strings, the language won’t recognise those expressions as type guards.

typeof v === "typename" and typeof v !== "typename", where "typename" must be "number", "string", "boolean", or "symbol".

While TypeScript won’t stop you from comparing to other strings, the language won’t recognise those expressions as type guards.

Okay, TypeScript recognize certain use of typeof as type guard, but what does it mean?

It means that when having a type guard:

TypeScript and JavaScript runtime are tied to the same behaviour.

Let’s take a look at:

1if (typeof amount === "string") {

2 value = parseInt(amount, 10); // **amount** type is string

3}Inside the if statement, TypeScript will assume that amount cannot be anything else than a string, which is true also at the runtime thanks to typeof JavaScript operator.

However, when looking at:

function formatMoney(amount: string | number): string {

TypeScript will try to prevent you to call formatMoney with anything else than a string or a number, however, nothing prevents you to do:

formatMoney({ myObject: 1} as any)

The cool thing here is that the typeof amount === "string" JavaScript operator usage will prevent the parseInt to be called with an object.

instanceof

The instanceof operator is also a type guard recognized by TypeScript, however, this one applies to function constructor (aka classes).

Here’s how is defined the behavior of the instanceof type guard in the TypeScript definition:

Here’s how is defined the behavior of the instanceof type guard in the TypeScript definition:

The right side of the instanceof needs to be a constructor function, and TypeScript will narrow down to:

1. the type of the function’s prototype property if its type is not any

2. the union of types returned by that type’s construct signatures

in that order.

User-Defined Type Guards: write your own Type Guard

As seen in the previous chapter, “real-world usage” of TypeScript is not restricted to scalar types (string, boolean, number, etc…).

Real-world applications mainly deal with complex object or custom types.

Real-world applications mainly deal with complex object or custom types.

This is when “User-Defined Type Guards” help us.

Let’s imagine an application with the following types.

1type UUID = string;

2interface Customisation {

3 recap_frequency: number;

4 favourites: string;

5}

6interface Billing {

7 name: string;

8 serial: string;

9 exp: string;

10 ccv: string;

11}

12interface User {

13 id: UUID;

14 first_name: string;

15 last_name: string;

16 plan: 'free' | 'premium'

17 customisations?: Customisation;

18 billing?: Billing;

19 primary_billing?: string;

20}

21// Mapped type tht get all User properties of User as required

22type PremiumUser = { [K in keyof User]-?: NonNullable<User[K]> };

23

- a User can be either free or premium.

- a PremiumUser is slightly different from a User object, it has always present properties, specific to a premium user: billing, customisations and primary_billing.

This makes sense because no user can become premium without giving a billing record.

Let’s see now what does it mean for our application:

1function getUserEmailRecapFrequency(user: User): number {

2 if (user.plan === 'premium') {

3 return (user as PremiumUser).customisations.recap_frequency;

4 } else {

5 return -1

6 }

7}For us, user.plan is “premium” means that user if a PremiumUser object.

Since we are not using Discriminated Unions, TypeScript doesn’t know that type could be inferred.

In order to indicate this type inference to TypeScript, we are gonna define a User-Defined Type Guards:

Since we are not using Discriminated Unions, TypeScript doesn’t know that type could be inferred.

In order to indicate this type inference to TypeScript, we are gonna define a User-Defined Type Guards:

1function isPremiumUser(user: User): user is PremiumUser {

2 return user.plan === 'premium';

3}

4

5function getUserEmailRecapFrequency(user: User): number {

6 if (isPremiumUser(user)) {

7 return user.customisations.recap_frequency;

8 } else {

9 return -1

10 }

11}Let’s took a close look to our first type guard:

1function isPremiumUser(user: User): user is PremiumUser {

2 return user.plan === 'premium';

3}- the type guard function argument type, like for overloads, should be as open as possible (in order to be used as much as possible)

Here user can be any kind of User. - we can notice a new is operator, called type predicate.

Basically, using in indicate to TypeScript that it can trust us on the return type (you can see it as a as for function return type).

— — —

Tip: Forget switch for redux reducers, use if with type-guards 🎉

Both type guards and Discriminated Unions are good features for redux reducers.

Community Runtime checking libraries

Now that you know how to build your own Type Guards, let’s take a look at what the TypeScript community accomplished with them.

Spicery

Manuel Alabor introduced this library in his interesting article entitled

“Pattern Matching with TypeScript”.

In this article, Manuel showed that Pattern Matching is achievable with TypeScript using his Spicery library, based on User-Defined Type Guards.

Let’s take a look at this library.

Spicery tagline is: “Runtime type safety for JSON/untyped data”.

In short, Spicery aim to provide runtime type safety for external data, which is a good point because, in a SPA, most of the untyped data comes from external APIs (XHR calls).

Since this library is no longer maintained, we will not go further on it, however I highly advise you to read Manuel Alabor article: Pattern Matching with TypeScript

io-ts

Introduced in the perfectly named “Typescript and validations at runtime boundaries” article @lorefnon, io-ts is an active library that aim to solve the same problem as Spicery:

TypeScript compatible runtime type system for IO decoding/encoding

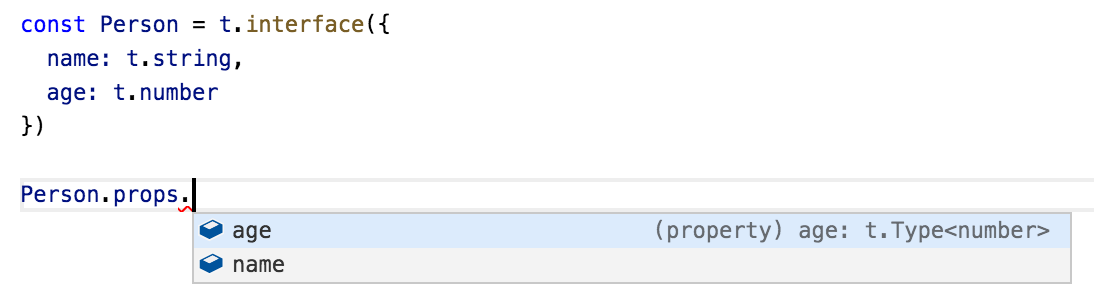

But how t.interface infer the argument object type?

Let’s look at t.interface definition:

1export class InterfaceType<P, A = any, O = A, I = mixed> extends Type<A, O ,I> {

2 readonly _tag: 'InterfaceType' = 'InterfaceType'

3 constructor(

4 name: string,

5 is: InterfaceType<P, A, O ,I>['is'],

6 validate: InterfaceType<P, A, O ,I>['validate'],

7 encode: InterfaceType<P, A, O ,I>['encode'],

8 readonly props: P

9 ) {

10 super(name, is, validate, encode)

11 }

12}

13

14// ...

15

16export const type = <P extends Props>(

17 props: P,

18 name: string = getNameFromProps(props)

19): InterfaceType<P, TypeOfProps<P>, OutputOfProps<P>, mixed> => {

20 // ...

21}

22// ...The powerful thing with this library is that t.interface() will return an InterfaceType class of type InterfaceType that will propagate the type of the given object to the props property and will also give you a Type Guard method called is() having a default implementation of a type guard based of object comparison.

io-ts enable also to alias/rename the inferred type by doing the following:

1interface IPerson extends t.TypeOf<typeof Person> {}

2

3// same as

4interface IPerson {

5 name: string

6 age: number

7}— — — —

While this io-ts might look “overkill”, if you’re dealing with data or complex SPA, you might want to make your types “real” and io-ts is the best way to reach this.

ts-runtime

ts-runtime take another approach to runtime type assertions by using transpilation.

Sharing the same goals as io-ts and Spicery, ts-runtime will transform your code at compilation, just like TypeScript or Babel already do.

From the documentation:

This function simply creates a number from a string.

1function getNumberFromString(str: string): number {

2 return Number(str);

3}The code below is the result, with runtime type checks inserted.

1function getNumberFromString(str) {

2 let \_strType = t.string();

3 const \_returnType = t.return(t.number());

4 t.param("str", \_strType).assert(str);

5 return \_returnType.assert(Number(str));

6}

While still experimental, io-ts might be a good solution if you want to keep your existing code less impacted as possible by runtime type assertions.

Appealed? you should go play with it on the ts-runtime playground.

Conclusion

TypeScript is not just a static analysis tool, in fact it is, but offers you the possibility of “making types reals”.

Type Guards is a beautiful and powerful feature of TypeScript that will allow your application to gain in maintainability and reliability.

We use cookies to collect statistics through Google Analytics.